By Patricia Chadwick

The globalization of economies—that of the U.S. as well as most of the rest of the world—began in earnest in the early 1980s when China was entering the global trading sphere. But as early as the 1920s, American companies had already started building manufacturing plants in Europe—both General Motors and Ford Motor Company were in Germany. Within the next couple of decades, American heavy equipment manufacturers—names like Caterpillar Tractor, Bucyrus-Erie and John Deere—built facilities in Belgium, the UK, and Germany. Those strategic capital investments were designed primarily to meet the demand for American-made hard goods, and, at the same time, to avoid the onerous tariffs associated with importing American-made machinery into Europe. A similarly high tariff was imposed on equipment manufactured in Europe and shipped to the U.S. Thus, the vast majority of the production by American companies in Europe was sold within the continent.

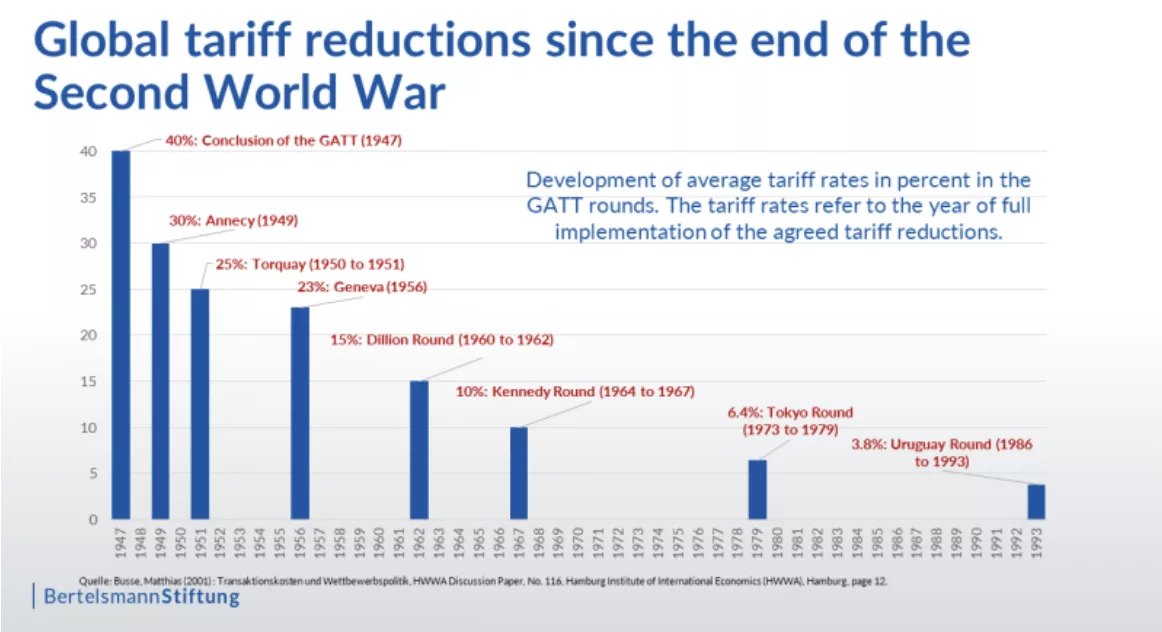

In the aftermath of World War II, a multi-national trade treaty, The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (also referred to as GATT and later as the World Trade Organization, or WTO) was established among twenty-three countries across the globe. Notably it did not include the three Axis powers, (all of which later joined), nor did it include Russia. The purpose of that treaty was to reduce global tariffs, and at the conclusion of the first meeting (in 1947), global tariffs were settled at around 40%. A quarter of a century later, the treaty included 102 countries, and by 1994, the count was 123. Over that period of time, from 1947 until 1993, the group met eight times, with each consecutive meeting reaching agreement to lower global tariffs, until by 1993, they were at 3.8%. See the nearby chart.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 fueled the opportunity for U.S. companies to augment their investments in Europe as well as export to a burgeoning marketplace. Over the subsequent thirty years, the continued thrust of globalization was a boon to countries on a global scale, but in particular to the U.S. In 2008, the GDP of the Eurozone was on a par with that of the U.S.—each with approximately $14 trillion. By 2023, U.S. GDP was nearly 100% higher at $28 trillion, while the Eurozone experienced a paltry 10% growth during that fifteen-year span. Over the same period, wage gains in the U.S. far surpassed those of the OECD (38 industrialized nations across Europe and East Asia) and unemployment reached a decades low of 3.4% in 2023.

The sudden and unprecedented imposition on tariffs this week—on more than 150 independent countries, notably excluding Russia—in some cases reaching more than 90%–brought my ninth grade civics class to mind. Wasn’t the power to levy tariffs the constitutional responsibility of the legislative branch of government? I knew I wasn’t wrong; however, what I had not appreciated, and what I learned from doing some research, was that, over the last 60-plus years, Congress has passed a number of laws that have expanded the President’s authority and latitude regarding tariffs. The last piece of legislation on that matter was in 1977, and since there is no member of Congress today who was also a member in 1977, I was out of luck in trying to reach anyone for an explanation of the rationale for that concession. It’s almost unfathomable to think that any member of Congress at that time would have foreseen the possibility that the President might raise tariffs by anything close to what has been done this week.

Trade deficits have commonly existed in the U.S. for decades and logically reflect the reality that the American economy is both largely consumption-based and has experienced greater income growth than countries in the rest of the OECD. On the other hand, the sizable trade surplus derived from the export of services—transportation, software, entertainment, government services, etc.—offsets much of the goods deficit. The purported reason for the President’s unprecedented tariff hikes is to put pressure on American industrial companies to relocate their manufacturing facilities to the U.S. However, for-profit companies in the U.S. are accountable to their shareholders, and the process of determining where and how much to make capital investments is largely a function of where the greatest return will be derived. Two important factors influencing that return on investment include: (1) the cost of capital and (2) the cost of labor. Heavy manufacturing is both capital and labor intensive, and the geographic disparity in labor rates around the world is an essential factor in determining where facilities will be constructed. The claim that manufacturing jobs in the U.S. have been lost is true. It is also true that the cost of labor in the U.S. is among the highest in the industrialized world. A recent report on CNBC’s Squawk Box shared the dramatic difference between the all-in hourly wages for autoworkers in North America. In the U.S., the rate is $70; in Canada, it is $40; in Mexico, it is $6. That staggering difference in labor cost explains why the auto industry spreads the cost of car production among the neighboring countries, rather than concentrate it in the U.S. Less capital intensive industries—e.g., companies that produce clothing and footwear—generally have far lower selling prices, making the input cost of labor of critical importance. The emerging economies of Asia, on account of their low relative labor rates, provide opportunity for better investment returns. Today, close to 100% of the world’s footwear is produced in Asia. Raising tariffs on imported footwear will not induce producers to move to the U.S. Those investments cannot be successfully uprooted and transferred to the U.S because the economies that exist, in Vietnam as an example, simply cannot be replicated in the U.S. Yet, the President has announced a 46% tariff on exports from that country.

Tariff policy as a “one size fits all” concept is foolhardy. Using a rifle, rather than a shotgun, approach feels like an option with more potential for success. But even a battle with China (the most obvious candidate to target) could wreak havoc with middle-class Americans, so many of whom run their own businesses and rely on Chinese imports because China is the only manufacturing source in the world for the goods they sell.

That being said, in just the last few years, there has been a significant increase in capital investment in the U.S. for an array of goods. That change was in response to COVID-19 in early 2020. The perilous impact on the economy is memorable—supply chain bottlenecks, lasting for months and in some cases well over a year, that wreaked havoc in every corner of the country. The U.S. was hostage to both foreign production and to shipping gridlock for products that were deemed essential to American security—largely components for high-tech/defense/health care industries. Sensing urgency, corporate C-suites accepted the reality that higher production costs were acceptable if only to ensure a secure source of goods for the domestic market. The popular notion of “just in time” supply chains had proven to be unreliable. In an about face, high-tech companies, and even the likes of Walmart, shared their plans to increase investment in onshore production. With the support of several pieces of Federal legislation, billions of dollars of reshoring investment began in 2021 and continues to this day. That trend by U.S. manufacturers has been augmented by foreign companies—a good example is the Taiwanese giant chip producer TSMC which is building extensive manufacturing facilities in Arizona.

Over the last seventy-five years, there has been a long and successful record of global reduction in tariffs. That trend has augmented economic growth, improved standards of living, enhanced labor participation on a global scale. Success doesn’t mean that the system is perfect, but perfection won’t be achieved with a broadscale application of tariffs that bear little resemblance to the underlying issues on a country by country basis, and it will likely cause massive economic harm before things get sorted out. And as this column goes to print, the President has just declared a 104% counter tariff on all Chinese imports. Holy Toledo!

Patricia Chadwick is a businesswoman and an author. Her first book (2019): Little Sister: A Memoir, tells the story of her growing up in a religious community-turned cult in the 1950s and 1960s. Her most recent memoir (2024), Breaking Glass, with the subtitle: Tales from the Witch of Wall Street, came out last May. It is a sequel to Little Sister and tells of her starting out on the lowest rung of the corporate ladder and succeeding in what was then the all-male bastion called Wall Street. www.patriciachadwick.com