By John Engel

This week we explore timely Decision-Making and Commitment as we reflect on 2024 and set goals for 2025. December is when the phone rings. “What’s my house worth?” and “When should I list?” and “How can I prepare?” people ask. Sometimes the timing is not to our liking; buying and selling is a reaction to a major life event. But for many, the decision is a choice with the luxury of time. There are many motivations and equally many paths to a decision.

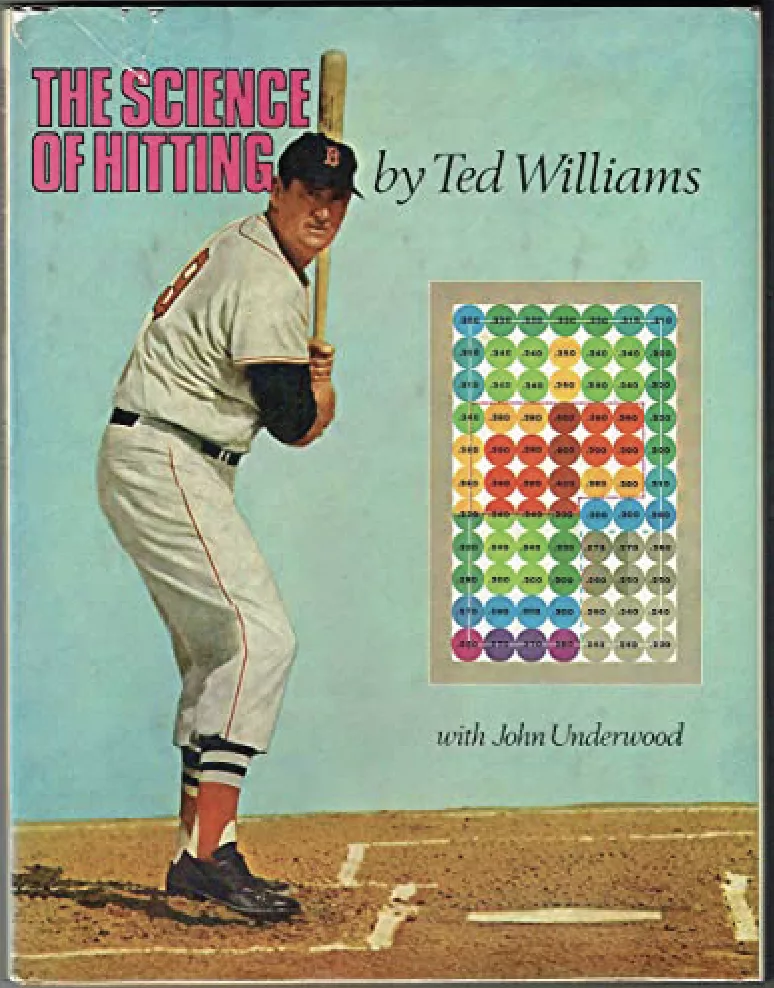

In his 1971 book, The Science of Hitting, Ted Williams describes the baseball player’s decision-making process when standing standing at the plate, “Everybody knows how to hit — but very few really do.” Ted is one of the greatest who ever played. His .482 on-base percentage is the highest of all time and his success, he argues, comes from being a student of the game, studying opponent behavior, and remembering past outcomes to predict the next pitch.

In the game of real estate — and life — we know it helps to study, to know context: info about the area, the seller, the listing agent, the other bidders, the competition, and recent sales. We make more informed decisions, aware that “past performance does not guarantee future results.”

The cover of his book features Ted Williams at the plate along with a color-coded grid showing his batting averages for any pitch. While Ted is a .400 hitter down the middle, he’s only a .230 hitter when the pitch is less than ideal. The baseball player makes his decision to swing in the first two tenths of a second, and he must swing at less-than-ideal pitches because in baseball there is what’s known as the “called strike.”

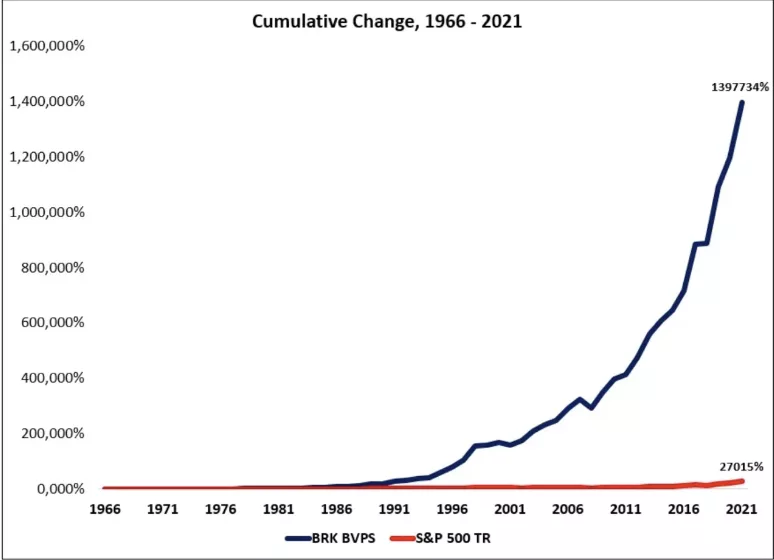

Warren Buffett refers to the book in his 1997 letter, saying the lack of “called strikes” makes his job easier than Ted’s. “We try to exert a Ted Williams kind of discipline…the business pitches we now see are just catching the lower outside corner. If we swing we will be locked into low returns. But if we let all of today’s balls go by there can be no assurance that the next ones we see will be more to our liking,” wrote Buffet. “Unlike Ted, we can’t be called out if we resist three pitches that are barely in the strike zone; nevertheless, just standing there day after day, with my bat on my shoulder is not my idea of fun.”

In the world of investing, there are no “called strikes.” You can wait for your pitch. If you don’t like the price of Bitcoin today, you can try again tomorrow. This is not the case in real estate. Today’s house will be gone tomorrow, but we can wait for the perfect house. While there are no “called strikes,” I wonder if decision-making changes in a market with so little inventory, and where demand outstrips supply. Some buyers play like Warren. They wait at the plate with the bat on their shoulder, waiting for the perfect pitch.

Warren concludes by reinforcing this idea of decision-making discipline, saying he only bets on what he knows and understands. If they gave every college graduate a punch card of only 20 decisions to make in their adult life, they’d think very hard about each of them, and he says it only takes four or five really good decisions to be considered fabulously successful.

Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize for his research on decision-making. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), he describes two systems.

Fast thinking is automatic, intuitive, and emotional. It works effortlessly, relying on instinct, gut reactions, and mental shortcuts (heuristics). Fast thinking handles routine, everyday tasks and snap judgments, but not the purchase of a house.

Slow thinking is deliberate, analytical, and effortful. It requires conscious effort and logical reasoning. This system is activated when we solve complex problems, evaluate arguments, or make difficult decisions.

Our brains default to fast thinking because it conserves energy and requires less effort. But fast thinking leads to errors in judgement. Daniel says take it slow, wait for your pitch.

But it’s possible to wait too long. Henry James’s masterpiece, The Beast in the Jungle (1903), tells the story of John Marcher, a man who lives his entire life believing that something extraordinary, a “beast in the jungle,” is destined to happen to him. He waits in anxious anticipation for this monumental event. It turns out the “beast” he was waiting for was not a life-transforming event; it is his failure to live, seize love, and embrace the present moment. It’s the story of decision-making and missed opportunities. Henry James says to swing that bat; he would have made a good realtor.

Robert Heinlein reminds us in his novel, Starship Troopers, “Doing something constructive at once is better than figuring out the best thing to do hours later.” This principle emphasizes the value of seizing the present moment, taking action with imperfect information, and learning through doing, rather than waiting for a “perfect” opportunity or plan to emerge. Heinlein’s quote promotes decisive action in the face of uncertainty, while John Marcher in The Beast in the Jungle embodies the tragic consequences of inaction and hesitation.

The military is the one example I can offer in contemporary society where timely decision-making is trained. “Make a decision, Lieutenant, make a decision!” In college and business, we are taught problem-solving and communication skills, and training on decision-making is a lost art. Not so in my house. My wife quotes this line at me more often than I would care to admit — “Make a decision, Lieutenant,” so for some of us, it is still being trained.

I recently sold a house in Westport to a young couple. They bought the first house they looked at, on the first day, for full price. While that may appear to be fast thinking, it’s a great house, they knew their own mind, and they made a great and timely decision. So many others tour dozens of houses over a span of years, make offers, even have their offers accepted and eventually get cold feet, pulling out of every deal.

Heading into 2025, let’s ask the experts: Ted Williams says study up, arrive prepared, and know your strike zone. Warren Buffett says be disciplined and wait for your pitch because there are no called strikes. Conversely, Henry James and Robert Heinlein will warn you against waiting too long. But what do they know? they wrote fiction for a living.

Notes from the Monday meeting: This weekend, I listed a house. Forty-three people toured, seven made offers, and six of them were competitive. The 7th stood out for spending three hours at the house before submitting a 58% offer. Nobody swings at the 58% pitch.

John Engel is a broker on The Engel Team at Douglas Elliman, and this month, the range of circumstances of his clients is quite extraordinary: five siblings settle and sell an estate; another sells furnished; while one was potentially under-water. Buyers are equally varied; from Denver to Norwalk to Tribeca, they look for an escape, a project, and sometimes just a home, upsizing, downsizing and right-sizing.