By Jim Knox

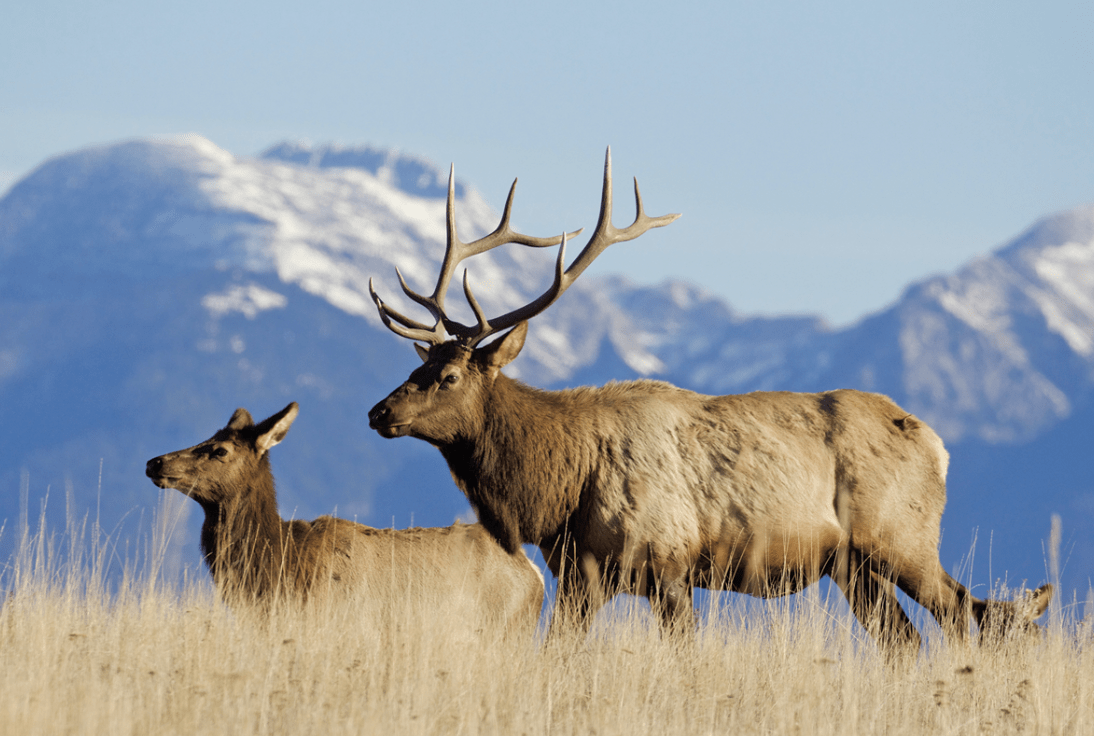

Their movement caught our attention, and we quickly pulled our caravan over on a shoulder overlooking the Yellowstone River. Their long cream and tan bodies deftly traversed the rounded shoulders of the river valley. With movement came recognition. Though similar, these creatures were clearly different from our antlered neighbors. These extra-large cousins of the White-Tailed deer pushed their way upslope and paused to survey us from an elevated vantage point.

The North American elk, Cervus canadensis, is an enormous deer—second only to moose in size. Females, known as cows, can reach 4.5 feet at the shoulder and attain weights up to 600 pounds. Males, known as bulls, are far larger, with maximum shoulder heights—and antlers—surpassing 5 feet, body lengths approaching 9 feet, and body weights of more than half a ton!

Also known by their Shawnee and Cree name, “Wapiti,” meaning “White Rump,” these giants range from a rich chocolate brown to a pale tan with a whitish rump easily identified from far afield. With 6 recognized subspecies in North America, and closely related species such as the Manchurian Wapiti in Asia and the Red deer in Europe, these giants of the deer tribe are found throughout the Northern Hemisphere in forests and forest-edge habitats.

Like their fellow wild creatures, elk confer profound benefits to the plant and animal communities they inhabit. In the national wildlife refuges where they have been reintroduced, elk have aided in the restoration of intact grass prairie ecosystems. Given their preference for grazing predominantly on wildflowers and grass, but also their browsing habits on shrubs and trees, elk stimulate the growth of native prairie plants while controlling shrub and tree growth.

A key secret to Elk success lies in the combination of physical and behavioral adaptations, especially in the first crucial days. Cows carefully hide their newborn calves for the first several days of their lives. Upon birthing their calves, cows find camouflaged areas in tall grass or dense brush in which to conceal their calves. Calves enhance this concealment by lying motionless for the first two weeks of life. Being born with virtually no scent to avoid attracting predators, calves evade most carnivores. Possessing white spots, which break up their outline and mimic dappled light, they are virtually invisible to the untrained eye.

Gregarious by nature, elk live in large groups called herds that can reach well into the hundreds and even thousands. Herds are matriarchal—dominated and led by a single cow. These social groupings provide testimony to the success of the massive deer, with Southern Yellowstone’s Jackson Herd reaching an estimated 11,000 elk!

Regarded as ultra-resilient mammals, elk are true survivors. Through focused conservation efforts and reintroduction, their numbers continue to increase thanks to conservation measures by wildlife agencies and private citizens like. In fact, the Rare California Tule elk was nearly lost to extinction before citizens and wildlife agencies took action—recovering the species from 4 animals in 1875, to more than 5,700 animals today!

Enormous, resilient, adaptable, and ecologically indispensable, elk command our attention. But, if we by chance overlook the stately deer, they remind us of their presence—by blasting a multi-note call known as a bugle from more than two miles away! Research findings from the University of Northern Colorado conducted in Rocky Mountain National Park suggest that these loud bugling calls of bulls contain much information. Bugles communicate many things including the bull’s residency in the area with his harem, as well as if the cows in the herd are straying too far, and perhaps most significantly—that the bull is willing to defend his cows in battle to the death!

What lessons do elk offer those that peer a little deeper into their world? Elk are both highly social creatures—seeking the protection of the eyes and ears of the herd—and also bold individuals who explore unfamiliar territory and proclaim their presence to a world of adversaries and competitors. Like the elk, we humans can benefit from such tact when confronting the dangers of an increasingly competitive world. These great deer also hold the power to restore the health of the living communities around them. We too hold this power, and with the elk as a living model, we can further aid in its recovery, which in turn restores the land and restores our faith in our ability to recover wild ecosystems. Wild, powerful, and an icon of the great American West, the elk stands as a rugged symbol of wilderness and its resilience. By giving the elk and the wilderness the chance and the support to recover, we are also giving ourselves that same chance to protect one another and achieve both the potential of the deer, and of what we hold most dear.

.Jim Knox serves as the Curator of Education for Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo and as a Science Adviser for The Bruce Museum. His passions include studying our planet’s rarest creatures and sharing his work with others who love the natural world.