By Jim Knox

I first heard the creature in the thick conifers bordering a stream flowing along the Connecticut-New York line. It sounded almost mechanical—like a pull-start motor catching and increasing in volume. I cautiously ventured into the woods to investigate. No more than 20 feet in, I was startled by the booming of air and hammering of wings as a large chicken-like bird exploded from cover and shot past me upstream.

That was my first encounter with an animal I would come to know well as wild neighbor over the years. The Ruffed Grouse, Bonasa umbellus, is a familiar creature to all who live and explore the north woods. Found from Alaska though most of Canada and down though the Appalachians and Rockies, the birds thrive in cool, forested habitats.

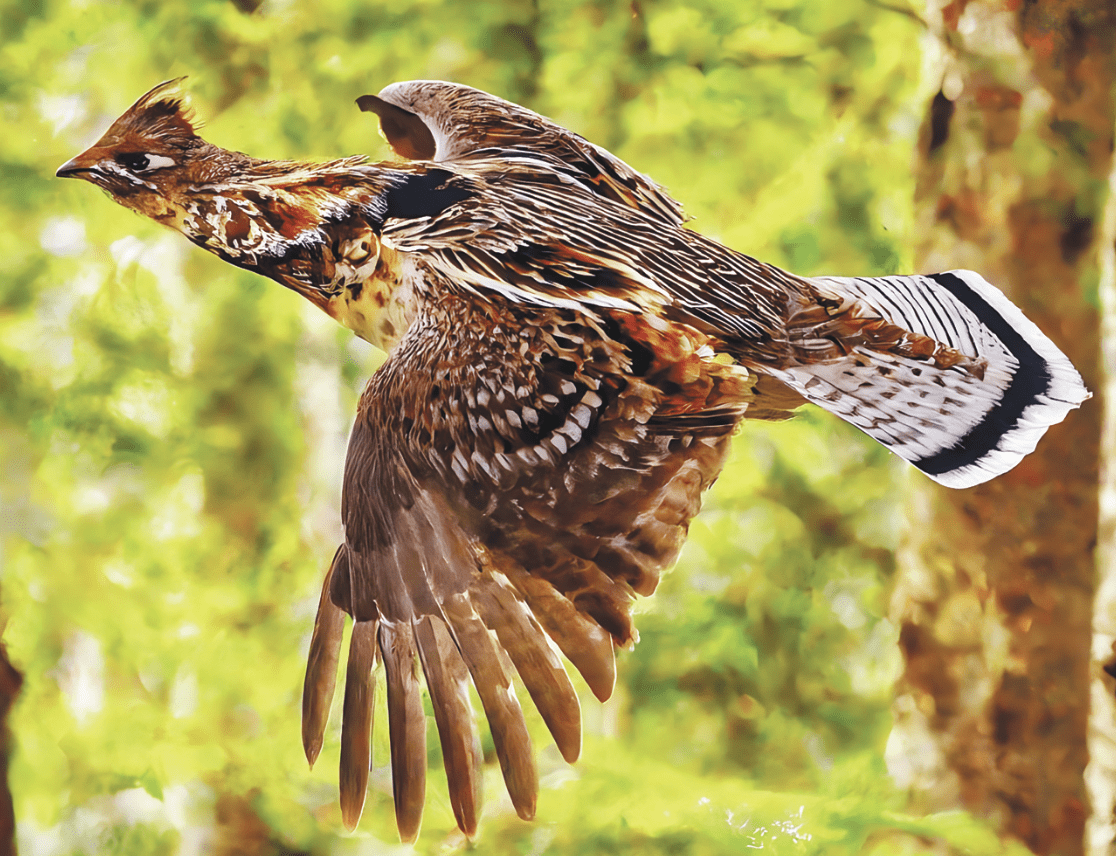

As one of Connecticut’s largest ground birds, growing to 20 inches in length and 1.6 pounds in weight, the Ruffed Grouse is little known to most, yet there is good reason for this. With the bird’s exceptional camouflaging plumage of dappled reddish or grayish feathers, the grouse melts into its forest habitat. Once detected, its signature triangular crest and dark bands near the tip of its fan-shaped tail confirm its identity. The grouse gets its name from its exceptionally long black ruff of neck feathers which the males erect when displaying to grouse hens or to proclaim and defend territory.

While the grouse is a hard bird to detect, it was greatly prized as a game bird from the time of the Colonial Period. In testimony to this, New York State passed one of North America’s earliest game management laws by closing a season to grouse hunting in 1708, to safeguard the bird’s population. In fact, the bird was so esteemed as table fare, its Latin name Bonasa means “good roasting.”

While it is one of 10 North American grouse species, the Ruffed Grouse is quite unique. Though it gorges on insects, fruit, and berries in summer, it shifts gears in season to digest bitter plants with toxic compounds that other birds cannot eat. This is especially advantageous during the harsh northern winters when food is scarce. It is during the winter the grouse comes into its own, consuming copious quantities of fibrous plant matter thanks to special adaptations including a seasonally enlarged crop for food storage. In the northern tier of their range grouse behave like their mammalian cousins, lynx, and wolves, burying themselves in soft snow drifts at night to take advantage of the protective cover and insulation.

Though these physical and behavioral adaptations equip the grouse with a keen survival edge over competitors and predators alike, the grouse possesses one more astounding cold weather trait—snowshoes…at least the Ruffed Grouse’s version of snowshoes. In response to plunging mercury and rising snowpack, the grouse grows comb-like projections on its toes, enabling it to displace its weight across deep snow, saving precious energy and keeping it “on its toes” against hungry predators.

This is not the bird’s only connection to snowshoes. Surprisingly, from Alaska to the mountains of West Virginia, the grouse’s range aligns almost exactly with that of the Snowshoe Hare. The populations of two species are linked beyond just their habitat preference. When hare populations increase, predator populations increase in response. As the populations of Canada Lynx and other carnivores rise, they hunt the abundant hares, driving their populations down. With hares scarce, the carnivores seek alternate prey in the form of plentiful grouse, driving down their numbers as well. This gives the prolific hares a chance to rebound, giving a reprieve to the grouse populations and the cycle begins anew.

The grouse hen is regarded as an especially good mother, keeping a sharp watch over her brood of up to a dozen chicks until they can fly and roost safely on their own. It is this strong parental tendency that leads larger gamebirds such as Ring-necked Pheasants and Wild Turkeys to parasitize grouse nests by laying their own eggs within them. The highly protective grouse hens raise the introduced pheasants or turkeys as their own, thereby increasing their odds of survival!

While the female seeks to avoid attention, the male employs an entirely different strategy. The males display by puffing their chests, extending their elongate neck ruff, and fanning their boldly patterned tails. They then rotate their wings forward and backward, creating small vortices and vacuums beneath the wings which create a signature sound. The loud, deep booming can be heard nearly half a mile away and has earned the bird the nicknames of “Drummer” and “Thunder Chicken.”

With its cryptic camouflage and unique cold-weather adaptations, the Ruffed Grouse is a true New Englander and a creature of enduring resilience found just over our stone wall.

Jim Knox serves as the Curator of Education for Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo and as a Science Adviser for The Bruce Museum. His passions include studying our planet’s rarest creatures and sharing his work with others who love the natural world.