By Jim Knox

“We got one!” my older siblings called out excitedly. Laser focused, undeterred by fleeting opportunities gliding around us, my brother Bruce and I locked on the location of the last yellow-green flash we saw and held our breath in excitement. Virtually invisible in the growing June darkness, our quarry too had gone dark, seeming to taunt us in our effort as we scanned our yard close to the inky wood line.

After what seemed like minutes, another brief yellow-green glow blinked on no more than 10 feet away and climbed toward the edge of our reach before blinking out once more. With the aid of a slightly brighter indigo sky as a backdrop, we spied the small creature rising ever higher. Without hesitation, we stretched up and—with a quick scoop—whisked it into our Mason jar. With a quick downward screw of the fork-punctured lid, we brought the jar to our 6-to-8-year-old eye-level and excitedly awaited confirmation. After another few seconds it happened. The soft unmistakable glow illuminated our faces, sparking another glow—that of our smiles. For a few brief moments that June night, we beheld one of nature’s wonders. A harmless, beautiful, and ethereal creature—it mesmerized us in that moment, just as its kin have mesmerized our species through recorded history.

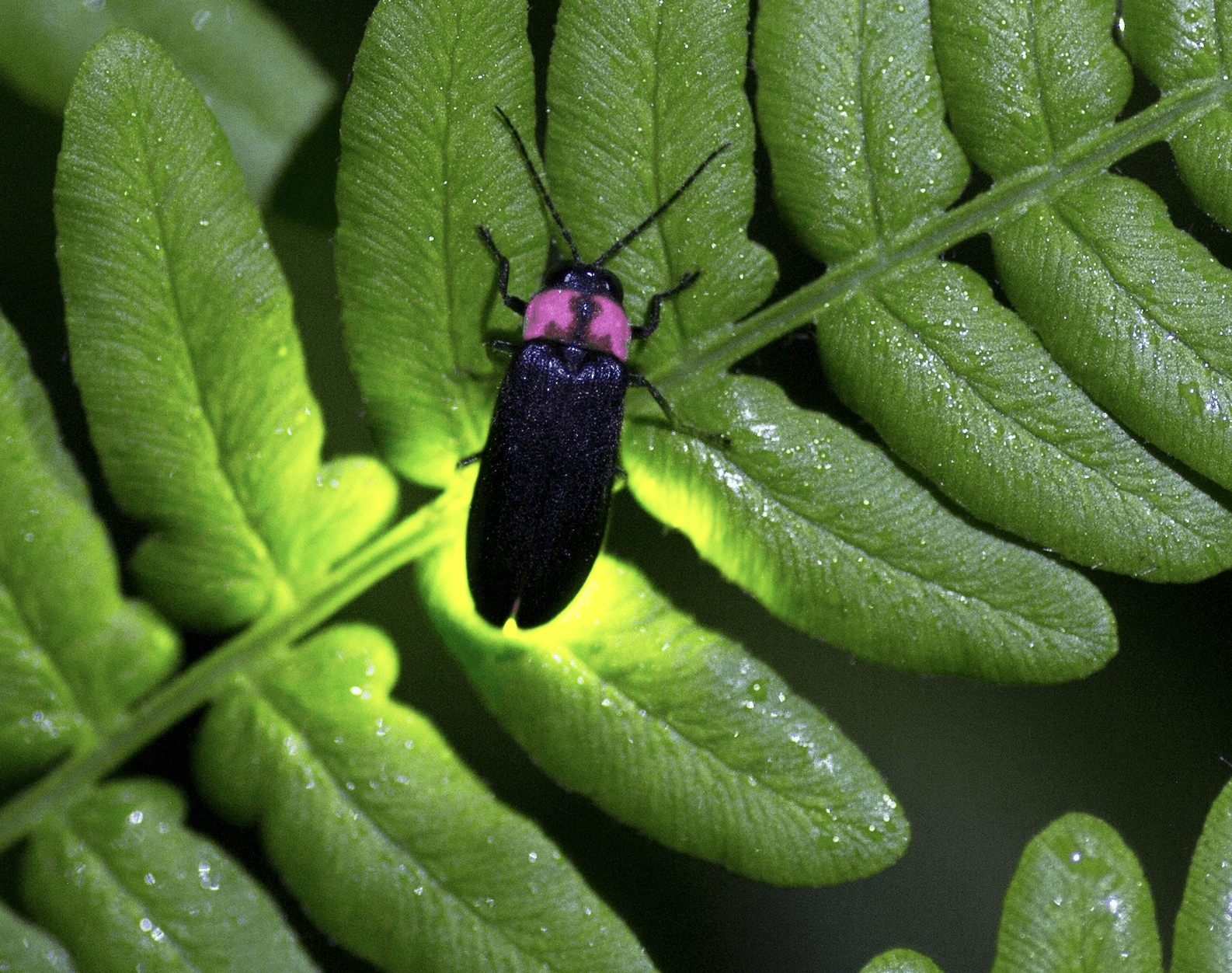

With a pedigree extending back 99 million years in the fossil record, and known worldwide in many guises, the firefly is not just one—but a family of some 2000 species. Members of this family, Lampyridae, include the glowworms and the lightning bugs with most bearing the hallmarks of nocturnal lives and bioluminescence (the ability to generate light). Of the 15 or so species native to New England, the most common and well known is the Eastern or Big Dipper firefly, Photinus pyralis. For generations, chasing lightning bugs has been a rite of childhood in New England—the unofficial start of summer marked by kids joyfully running across their yards in search of these harbingers of the season.

Lighting up the night. Beckoning us. Lightning bugs capture our fascination and seem to spawn a new question with each flash of light. What are they exactly? Why do they light up? How do they light up? While we know these answers, with more species being discovered, new questions emerge.

Lightning bugs are soft-bodied flying beetles. While the strategy varies by species, most Lightning bugs flash their light display to attract a mate. Typically, males flash their signals in flight, while the flightless females signal back to locate one another. The signaling flash characteristics are quite complex. Color, duration, timing, frequency, repetition, direction, and flight height vary among species and by geography. Possessing the remarkable ability of bioluminescence, Lightning bugs “light up” due to highly specialized adaptations. These insects utilize luciferase, a collective class of enzymes which function in light producing organs in their abdomens. Ranging from red, to yellow, green, and even pale blue, Firefly “cold light” does not produce any infrared or ultraviolet frequencies and is used in medical research and forensic science.

Favoring wetlands and forests throughout the planet’s tropical and temperate regions, Lightning bugs thrive in these insect-rich habitats. Feeding on soft-bodied prey such as worms and slugs, Lightning bugs spend much of their time underground or in leaf litter. In the larval glowworm phase, lightning bugs prey on insects and other invertebrates and true to their name—they all glow. This is a form of aposematic or warning coloration and display to all potential predators. Many lightning bugs produce a steroid known as lucibufagin. With a chemical signature similar to bufotoxin—a potent toad poison, this compound protects lightning bugs from most predators…but not all.

Certain “femme fatale” lightning bugs in the genus Photuris mimic the light signaling patterns of the distasteful, lucibufagin-laden male Eastern Fireflies, luring them in. When a male touches down next to the false female—she strikes, eating the male and sequestering his toxin to use for her own protection from predators, including amphibians, birds, and mammals!

Though tested by time, lightning bugs suffer from habitat loss, climate change, light pollution, and a host of factors. Yet, in areas where conservation measures are stringent, their populations remain strong.

Beautiful, potent, timeless, beneficial, Lighting bugs have a lot to offer us. By refusing to conform to any one conventional description, these fascinating creatures teach us that we too can perform beyond any narrow definition. Armed with this knowledge, and this example, we humans can strive to exhibit our personal beauty, strength, and resilience simultaneously. We too can utilize our unique abilities to innovate, advancing knowledge and benefit to those around us. With a 99-million-year model of success to study, we’ve got a running start. It’s not always easy, but anything’s possible…when you follow the light.

Jim Knox serves as the Curator of Education for Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo and as a Science Adviser for The Bruce Museum. His passions include studying our planet’s rarest creatures and sharing his work with others who love the natural world.