Perhaps no animal is more synonymous with spring than the rabbit. Throughout recorded history, it has served as both harbinger and metaphor for the season of life, renewal and growth. Though active year ‘round, rabbits breed, reproduce and flourish with the coming of the spring season.

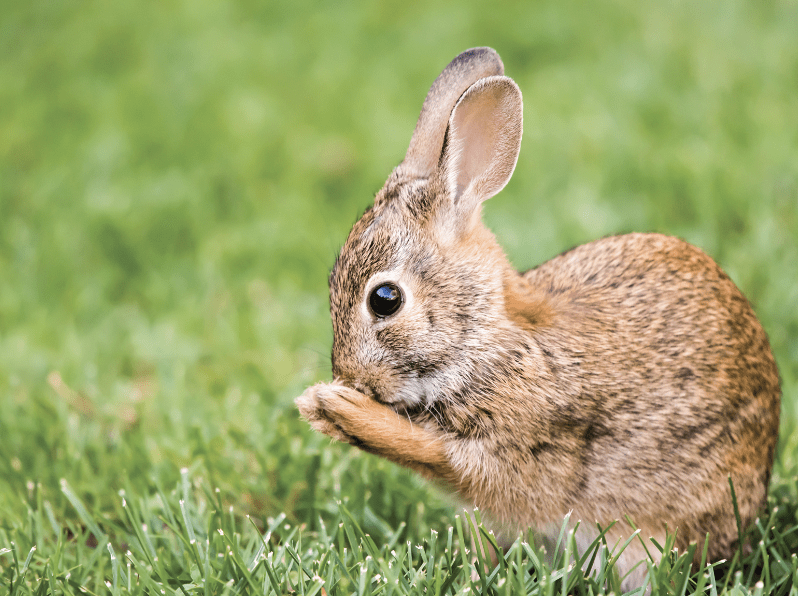

To most, the rabbit is a generic creature identified across cultures by it’s small brown body, long ears and hind legs, and overall adorable appearance. A closer look in our own backyard reveals a creature which deserves special attention, and even study.

If you ask most Connecticut residents the identity of the cute bunnies doing their utmost to eat the contents of their gardens, they’d identify the “Cottontail” as the culprit. They’d be right, at least generally. But there is more to this little beast than a casual glance may render.

The Eastern Cottontail Rabbit, Sylvilagus floridanus, is abundant throughout Connecticut, and does indeed make return trips to Fairfield County’s all-you-can-eat suburban salad bar. This is the species we see grazing along the green shoulders of the Merritt Parkway and zipping into hedgerows at the slightest approach. Yet, despite its familiarity and seeming omnipresence, this creature is no native New Englander.

That distinction is owned by its discrete, more reclusive cousin. The New England Cottontail, Sylvilagus transitionalis, is the only rabbit native to Connecticut, New England and neighboring New York. It was the rabbit known to English colonists as a coney, and is thought to have inspired the name Coney Island, for its great abundance on the island in the 1600’s and 1700’s.

While this native New England rabbit was uniquely adapted to the habitats and natural habitat succession of New England, development and land practices altered the landscape. With the introduction of the more adaptable Eastern Cottontail from other regions of the country in the early 1900’s, the native found itself with stiff competition for limited resources.

Closer scrutiny reveals two distinct creatures. The New England Cottontail is a creature of forests, specifically transitional forests, known as thickets. Naturally, these occur in the aftermath of forest fires, floods and severe storms. These rabbits thrive in the dense cover of these regrowth areas. They rarely stray far from that cover and their eyesight is designed to detect potential predators at close range.

The Eastern Cottontail, by contrast, is a creature of open spaces. They prefer grasslands and meadows, as well as their manicured counterparts such as parks, lawns and golf courses. In short, they were practically designed for suburbia.

While these close-cousin species share excellent hearing, sense of smell and swiftness of foot, one key adaptation makes a world of difference–eyesight. With eyes approximately 50% larger than their thicket-dwelling cousins, Eastern Cottontails hold the advantage in human-altered New England. With such distance vision, they can venture further from cover to access plentiful grasses while still tracking potential predators from a safe range. Likewise, they are the look-alike cousins who invade our gardens and scurry under our fence lines.

Though both species are approximately 14-19 inches in length and up to 2.5 pounds in weight, the unique traits of the New England Cottontail include: smaller ears, fine black fur lines along the edges of those ears and a black star at the crown of the head. Sadly, these specialists have lost approximately 85% of their home range in New England and they need our help.

Thankfully, there is hope for their recovery. Study has revealed no evidence the species are hybridizing, and there are those who are coming to the aid of their wild neighbors in need. Through programs like the Young Forest Habitat Initiative and other restoration efforts, The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection is conserving essential rabbit habitat. Given that 90% of our state’s land is privately owned, citizens are making all the difference. By working with our state wildlife agency, our neighbors are managing their land to benefit New England Cottontails, along with native songbirds and amphibians. Additionally, groups such as The Catherine Violet Hubbard Wildlife Sanctuary have adopted land use practices which actively conserve native rabbit habitat right here in Fairfield County.

While an adorable appearance never hurts a marketing campaign, it doesn’t speak to conservation merit. Yet the evolutionary wealth of native species is not to be dismissed. The plants and animals native to a region are the ones uniquely designed to survive amidst the conditions and environmental challenges of that region. More specifically, protection from introduced diseases and species often reside within the physical and behavioral makeup of our wild neighbors. By protecting them, we not conserve native biodiversity, we also promote our own resilience.

So the next time you see that adorable icon of spring, remember there’s more to them than meets the eye…and the ears.

Jim Knox serves as the Curator of Education for Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo and as a Science Adviser for The Bruce Museum. His passions include studying our planet’s rarest creatures and sharing his work with others who love the natural world.