Tuesday 26 March (Jacek Dolata)

By Annali Hayward

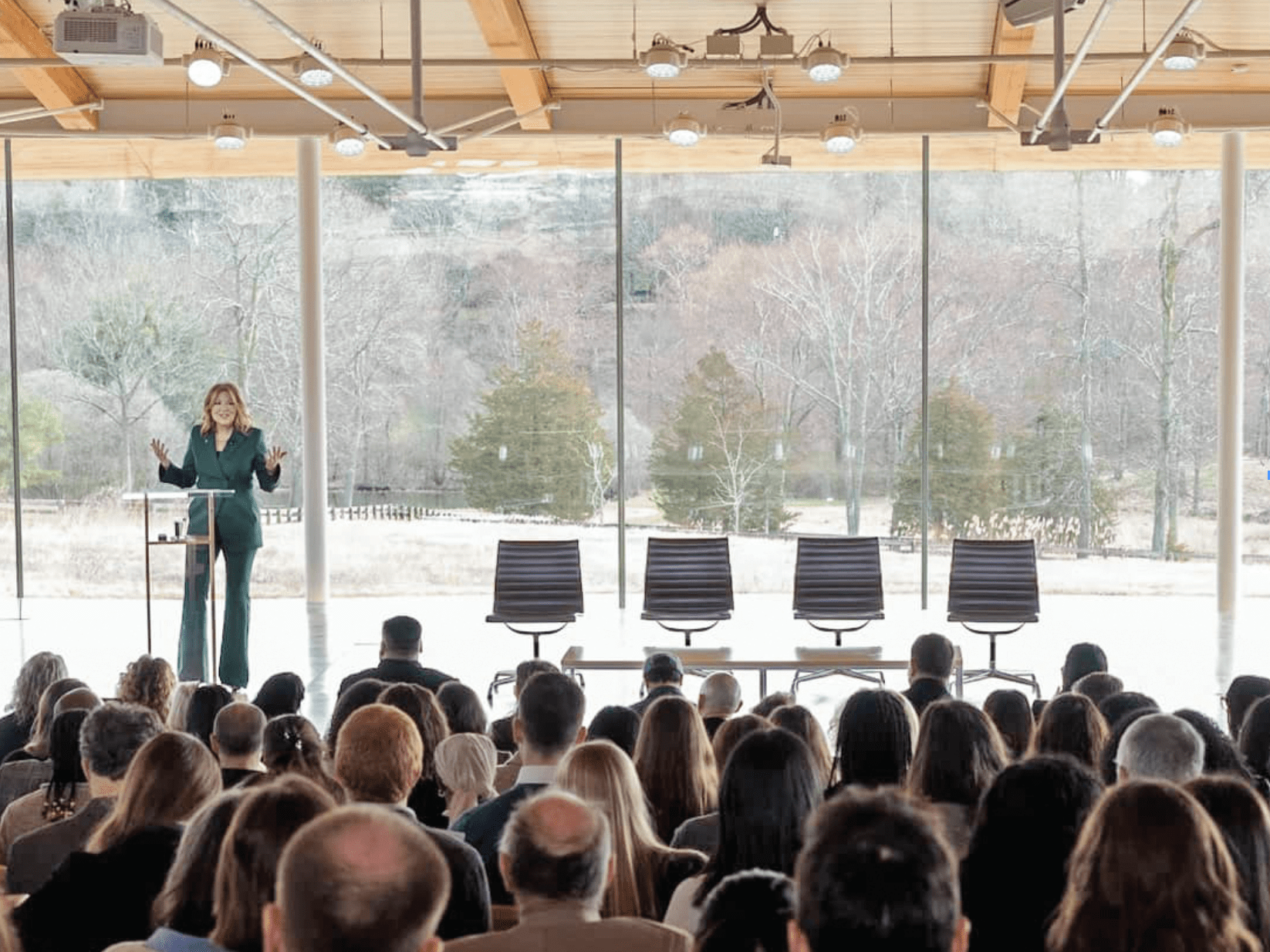

A global movement continued to swell last week from New Canaan’s corner of the world, in the form of the third annual Design for Freedom Summit at Grace Farms.

The target? Modern slavery, which ensnares some 28 million people worldwide in forced labor — an estimated $150 billion criminal industry.

Over 550 members of the building, construction and raw materials industry gathered at the 80-acre site Tuesday, for a summit on the insidious practices that often go unseen through the built-environment supply chain.

“This is a time that we are just accepting ‘slavery discount,’” said Sharon Prince, CEO and founder of Grace Farms, in her opening remarks.

“First the food industry was called to be accountable, then clothing — today, shelter is being called to account,” said Prince, who began the Design For Freedom summit in 2020 to re-imagine architecture in a more just world.

Prince told attendees that these practices produce an estimated $63 billion worth of goods for those in the industry to consume: “Our sisters and brothers would not be enslaved if we refuse to touch that mammoth amount of tainted goods.”

Kicking off the day with her searing portraits of people around the world engaged in backbreaking, life-threatening forced labor was Lisa Kristine, a renowned humanitarian, photographer and founder of the Human Thread Foundation. Her pictures of children carrying slabs of slate bigger than themselves — “slate like I have in my house,” said Kristine — drove home the desperation that many architects and their customers never see. There was barely a dry eye in the house as she concluded with the words of her “old friend” Archbishop Desmond Tutu, ‘none of us are truly free until all of us are finally free.’”

If Kristine set the tone for the day, the moderators, panelists and speakers after her took it as a call to action. What followed was at times blistering commentary on the blindness of ever-more outdated sourcing and supply chain practices, as well as laws and policies that do not go far enough, combined with innovative ideas and insight into tackling the issue.

Panelist Leonardo Bonanni explained how his company, Sourcemap, uses tech to help manufacturers map, monitor and verify that the sources of their raw materials are conflict-free. One of their customers, Shaw Industries, relies on that technology. VP of Sustainability Tim Shaw reflected on how industry understanding of sustainability has moved on in the past ten years. “It had everything to do with things: objects, stuff,” said Shaw, but now it is becoming much more about “who are the people behind it.”

But, true to form for Grace Farms, there is more to the story. The next panel of experts tackled the question of how to fight modern slavery in a world — and an industry — that is also tasked with rapid decarbonization.

Combining seemingly disparate issues and perspectives is par for the course for Prince, whose principle that “space communicates” underpins the work of the Grace Farms foundation in bringing together the worlds of the arts, justice and community.

Accordingly, for those at the summit, the challenge was posed to continue to meet client demands in “driving costs lower and trying to meet our budgets and timelines,” as Prince said, while striving for zero-slavery materials, all while reducing their carbon.

Indeed, eight percent of the world’s carbon is emitted through concrete cement manufacturing and another eight percent through steel, said Fiona Cousins, director and Americas chair for global engineering firm Arup. Cousins sat on a panel with Hind Wildman, a director at the Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture, which has recently produced a report that gives guidelines for how to reduce carbon in the built environment, based around the framework of “avoid, shift and improve,” according to Wildman.

The drive for change was evident among the attendees in the sinuous River building’s Sanctuary auditorium Tuesday. Indeed, 75 students from 30 universities were present, representing those at the beginning of their careers with “immediate agency to prioritize ethical supply chains on [their] first job,” said Prince.

As Shaw said, in reaction to Kristine’s stories, “[it] broke my heart a little bit…but never inspired me more to continue to do this work.”